When Experiments Become Bad Habits

Your 'temporary' solutions probably aren't temporary—and here's how to tell. Experiments are great, but without a clear exit strategy, they quickly become the new (and often broken) status quo.

I watched an organization run the same "experiment" for three years.

The "Agile Coaching without Scrum Masters" model - where a single coach tries to cover multiple teams that should have dedicated Scrum Masters - started as a budget-driven staffing compromise. Capacity constraints, urgent organizational pressure, a gap that needed filling fast. The conversation went something like: "We'll try this lean approach for a quarter and see how it goes."

That was 2023. They're still running it. And they still call it an experiment. The irony? The experiment eventually "succeeded" by eliminating the need for coaches entirely - including me. When your band-aid becomes the standard, you stop noticing the wound.

Nobody wants to say this out loud: most organizational "experiments" are permanent decisions wearing temporary costumes. The language of experimentation creates plausible deniability. Call it an experiment, you never have to formally commit. You also never have to formally kill it.

The Permanent Band-Aid

I see this everywhere. A team implements a workaround to handle an immediate problem. Maybe it's offshore support to reduce costs. Maybe it's a contractor model to handle capacity spikes. Maybe it's a modified process that "temporarily" bypasses the standard workflow.

The workaround works well enough. Not great - but cheaper than doing it "right." Every month that passes, two things happen:

- The invested effort makes abandonment feel wasteful (hello, sunk cost fallacy)

- The organization builds dependencies around the workaround

Within 18 months, your experiment isn't an experiment anymore. It's your operating model. You're stuck with it.

Research on organizational inertia confirms what you probably suspected: mature organizations have an inherent tendency to maintain their current trajectory - even when that trajectory was never formally chosen. Researchers call this "resource rigidity" (unwillingness to reallocate) and "routine rigidity" (inability to alter established patterns).

The numbers are alarming. According to industry studies, 50% of outsourcing relationships fail within five years - but many limp along for decades anyway. Only 16% of software projects finish on time and on budget, yet the approaches that produced those failures become "how we do things here."

Four Questions That Separate Experiments from Habits

Want to know whether your "experiment" is actually a habit in disguise? Ask these four questions:

1. Are you still in the Satir curve - or have you already reached the new status quo?

Virginia Satir's change model reminds us that all change involves a period of chaos before integration. Sometimes what looks like failure is just the messy middle. But here's the trap: organizations use the Satir curve as an excuse to avoid evaluation. "We're still in the chaos phase" becomes a permanent excuse.

Ask yourself: Do we have a clear picture of what integration looks like? Can we distinguish productive struggle toward a defined destination from aimless wandering? No clear end-state vision? You're not navigating the Satir curve. You're just lost.

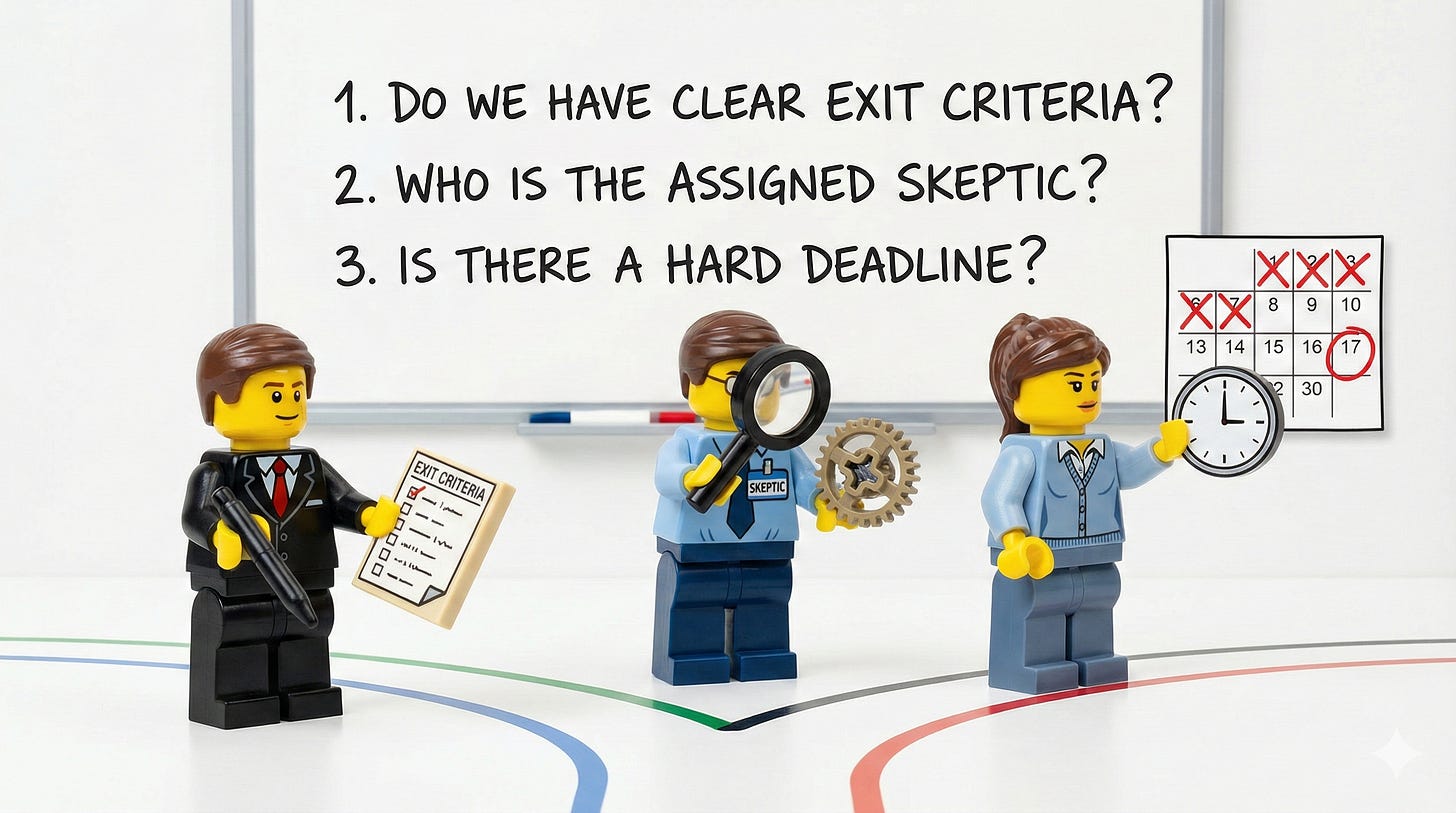

2. Can you name the specific criteria that would trigger a change?

Real experiments have success criteria AND failure criteria defined before they start. Not after. Not "we'll know it when we see it." Actual numbers, dates, thresholds.

And "ending" doesn't necessarily mean reverting. It might mean modifying the approach, adjusting success criteria, or pivoting to something different. The point is having clear signals that trigger deliberate re-evaluation - not drift.

Can't articulate what would cause you to change course? You've made a permanent decision.

3. Who has the authority and the incentive to end it?

Often the person who championed the experiment has emotional attachment to its success. That's the worst person to evaluate it objectively. The people experiencing its failures - the teams living with the consequences - often lack the organizational power to pull the plug.

Who in your organization is actually empowered AND motivated to call this thing?

4. When is the next scheduled evaluation - and who's accountable for it?

Calendar it. Assign it. No evaluation on someone's OKRs means no evaluation happening. Experiments without scheduled checkpoints become permanent by default.

Missing any of these four elements doesn't mean you have an experiment. It means you have a habit you haven't admitted to yet.

Why We Call Habits "Experiments"

Language does heavy lifting here. "Experiment" is a loaded word in most organizations. It implies innovation. It suggests we're trying new things. It creates psychological safety - "this is just a test, we can always go back."

That psychological safety is exactly why we overuse it.

Calling something an experiment lets us avoid the harder conversation: "We can't afford to do this right, so we're going to do it halfway and hope nobody notices." That's an honest conversation. Uncomfortable, but honest. So instead we say "let's try this and see."

Three years later, everyone's still seeing.

The counterargument I hear most: "Some experiments genuinely need time to mature." True. But that's precisely why you need exit criteria before you start. Not to kill experiments prematurely - to protect them from becoming un-killable. An experiment with a scheduled 6-month review can iterate and improve. An experiment with no review date just drifts into permanence.

Breaking the Cycle

Before your next "temporary solution" becomes your next permanent headache:

- Define the exit criteria before day one. What would success look like? Failure? Write it down. Make it specific. "It'll save money" isn't criteria - "We'll reduce support costs by 25% within 6 months while maintaining SLA compliance" is criteria.

- Assign a skeptic to the evaluation. Not the person who proposed it. Someone with nothing at stake in its success. Their job: honestly assess what's working and what isn't.

- Create a sunset clause that requires action to continue. Don't make continuation the default. Make it the choice. Every 90 days (or whatever makes sense for your context - though I'd push back if you say longer than 120), someone should have to actively decide to keep going. Passive continuation is how experiments become habits.

- Budget for the "real" solution. If your experiment is a cost-saving measure, acknowledge you're trading quality for budget. Track what that trade-off actually costs you. The 26% average savings from outsourcing look less impressive when you factor in hidden costs, management overhead, and quality issues.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Your organization probably has half a dozen "experiments" running right now that stopped being experiments years ago. Budget constraints presented as innovation. Workarounds rebranded as agile adaptations. Band-aids that everyone calls temporary but nobody ever removes.

It's not because people are dishonest. Admitting a band-aid failed requires admitting the wound still needs treatment. Treatment is expensive. And in some organizations, admitting failure is culturally impossible - career-limiting at best, career-ending at worst. So the band-aid stays.

But pretending an experiment is still an experiment when it's clearly become your operating reality? That's more expensive. You're optimizing around a solution you never actually chose. Building systems on foundations that were supposed to be scaffolding.

Writers have a phrase for this: "Kill your darlings." The things we're most attached to are often the things we most need to cut. Same is true for organizational experiments. The more invested you are, the harder the evaluation - and the more important it becomes.

The question isn't whether y'all have these phantom experiments running in your organization. You do.

The question is: what would it take to actually evaluate them?

Try this Monday: Pick one "temporary" solution your organization has been running for more than a year. Answer the four questions. Write down what you find.

Continue Your Journey

AI Development for Non-Technical Builders: Learn to build intelligent tools without writing code - including automated decision systems that actually evaluate what's working.

Free Resources: More frameworks for agile coaches fighting organizational inertia.